Horses will always like beer

undeterred by any warning labels

We horses don’t drink as much as humans. Mostly, all I need to do is to walk down to the creek and take a few sips and I’m all set for the day. I don’t really understand the kids’ excitement when they get some of those sugary slurries. I can get my nutrients from other sources. There is one exception, though. Sometimes, Jake fills our barrel with beer. When he does so, I don’t linger, I’ll be right there to have some. Nothing tastes as good as liquid grains!

We don’t get beer that often, but when Jake last filled our barrel, he said “If we keep filling this up, we’ll soon have to put some hazardous chemical warnings on it. Toxic, corrosive, carcinogen, they say.” My reaction was “What?! I’ve been drinking beer forever.” I can feel for myself what is good for me and, boy, I like beer! I could not understand where those warning signs for beer could be coming from?

The last decade has witnessed a war on alcoholic beverages spurred by an opaque web of governments and nonprofits, all of which either conduct or fund research with the predetermined outcome that drinking alcohol is bad “from the first drop.” This culminated in the recent statement from the World Health Organization that “no level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health.” Sure, we all know that alcoholism has bad health consequences beyond the addiction itself and can lead to a variety of negative outcomes, such as liver cirrhosis. I will gladly believe that consuming massive amounts of alcohol can also lead to throat cancer.

The picture may be more nuanced, though, in the case of casual consumption of moderate amounts, which is why many “health authorities” maintain safe drinking levels, even today. Hyperbolic statements such as “alcohol causes cancer from the first drop” should only heighten suspicions about their motivation. Even highly carcinogenic compounds, such as benzene, have the property “taste” listed on certain specification sheets, which implies that back in the day, scientists actually consumed drops of such substances. Yet pioneer chemists were not all reported to have died of instant cancer. If consuming a drop of benzene does not cause instant cancer, then for sure a drop of ethanol does not either. Therefore, such hyperbolic statements being promulgated by “health authorities” and other “experts” in mainstream media, seems to have all the hallmarks of a concerted disinformation propaganda campaign, rather than a public health policy based on solid science.

Further presence of propaganda can be seen in the sudden rise of hollow slogans, with an increasing number of months being associated with the habit of staying dry. The onset of such months, such as “Dry January” or “Sober October” is typically accompanied by a slew of pompous anti-alcohol statements. This January was no exception. Ushering in “Dry January,” The University of Victoria released an online tool named Know Alcohol that will calculate how much individuals shorten their lives as a function of the amount of alcohol they consume. Let us at first point out that the interface is merely the output of a model, whose predictions are uncertain. By omitting that the results on the page are estimates, the managers of the site knowingly manipulate a subset of its visitors, who are not familiar with statistics or modeling and may therefore be deliberately misled into thinking that the results presented are deterministic.

However, issues with Know Alcohol go beyond the way the results are presented. In their press announcement, the researchers behind Know Alcohol stated having based their tool on the model the Candian Centre for Substance Addiction (CCSA) used to update its safe drinking limits. That move followed the footsteps of similar reduced assessments of safe drinking standards by their British and Australian equivalents. The CCSA concluded that they needed to reduce their guidance of “safe” drinking amounts from two beers a day to a puny two beers a week, based on their “rigorous analysis of recent science.” However, Wild HorseWisdom analyzed their technical reports ans showed that their methodology was all but “rigorous” or “scientific.”

At first, the CCSA ignored all studies that showed benefits from alcohol consumption. They then proceeded by selecting only sixteen out of over five thousand studies that link alcohol negatively to certain health outcomes. While discarding over 90% of the studies considered, they did keep two studies in the pool that correlate alcohol consumption to the negative outcome of … accidents (one on traffic accidents and another one on general accidents). Finally, they fed the results from each of these studies into a model that targets to predict the population-level “years of life lost” (YLL) as a function of alcohol consumption. I conjecture that they decided to keep the studies on traffic accidents in the pool just because tragic traffic accidents can kill very young people and therefore, those studies boost the YLL effect alcohol may have, much more so than studies that link alcohol to cancer.

However, even as the CCSA constructed a model based on inputs including a study on traffic accidents, the result was all but convincing. In fact, interpreting their own graph leads one to the conclusion that a person who drinks according to their old guidance of fourteen beers a week, will live on average to the age of 81.6, whereas a person who adheres to their new guidance of only two beers a week, may live to the shockingly older age of 82.1. The difference in YLL between the CCSA’s old and revised safe limits is not impressive. In fact, the CCSA’s report could reasonably have concluded to keep the safe drinking limits unchanged. Then why did the CCSA change their guidance? Because they set the arbitrary target of a maximum of 17.5 YLL, which in their model, corresponds to consumption of two beers a week. Why exactly 17.5 YLL is never explained. In fact, their modus operandi smells pretty much like having had the predetermined outcome that safe limits had to be reduced to two beers a week, for which then a “rationale” needed to established using models based on cherry-picked inputs and arbitrary cutoffs.

If the KnowAlcohol tool is based on the CCSA’s model as they say it is, those are the numbers it should produce. According to Know Alcohol, the result for a forty-five year old male who drinks fourteen beers a week, which was deemed “safe” by the CCSA as recently as last year, is that every single beer reduces his lifespan by 9.9 minutes. If we assume that that person continues to do so for another forty years, than the cumulative effect of all beers consumed would be a life reduction of (9.9 minutes / beer *14 beers / week *52 weeks / year *40 years)/(60 minutes / hour *24 hours / day *7 days / week *52 weeks / year) = 0.55 YLL. This estimate aligns with the CCSA’s model indeed. However, the CCSA’s model is based on population level estimates. It would be very bad practice to draw conclusions on an individual case level based on population aggregates, even if we hadn’t raised questions about the input data. I would qualify Know Alcohol as “highly misleading” and an implementation of Robinson’s paradox.

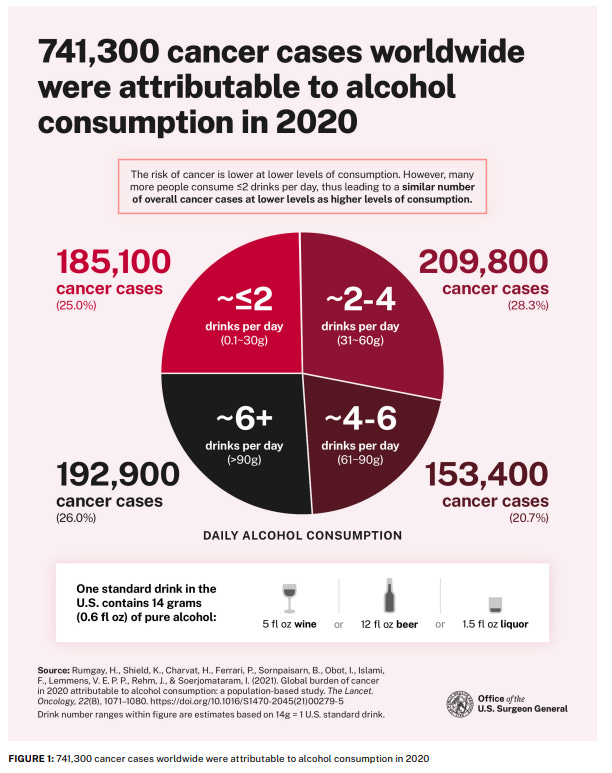

While Australian and Canadian authorities have been focusing on establishing “safe” drinking limits based on cherry-picked “evidence,” the United States’ contribution to “Dry January” was of another kind. Just two weeks ago, US (outgoing) Surgeon Genral Vivek Murthy held a press conference in which he announced a new HHS Advisory on Alcohol and Cancer Risk. The advisory states that alcohol is a “leading preventable cause of cancer and contributes to a hundred thousand cancer cases per year” and concludes by recommending that “the Surgeon General’s health warning label on alcohol products be updated and be placed more prominently on the container.” All of this has purportedly been deduced from “strong causal evidence.” So how strong is that evidence?

The health advisory’s Figure 1 prominently portrays the “fact” that 741,300 cancer cases were attributable to alcohol worldwide in 2020 and then breaks them down by the amount each person drinks. However, when I see that title, a few questions come up. At first, why does the US Surgeon General show global, rather than US estimates? Does that mean he just copied the numbers from elsewhere, rather than having research conducted by his own institution or academic affiliates? Secondly, just like the Know Alcohol tool, the result of 741,300 cases in 2020 is presented as an exact number rather than an estimate. The number of 741,300 seems awfully precise to me. Why are no uncertainties reported for what is obviously an estimate?

The answers to these two questions are straightforward. In fact, the footnote to Figure 1 shows the source of the “741,300 cases” claim, which is a 2024 paper in The Lancet Oncology, notably mainly by foreign scientists. So, no, in spite of its humongous budget, the Surgeon General did not bother commissioning any research, but just relied on a single paper reported elsewhere. Even more shockingly, that paper does not stand out by its scientific rigour. The approach used by the authors is to combine information from three data sources:

the number of cancer cases by country in 2020,

a risk ratio (RR) that relates alcohol consumption to cancer risk, which is taken as a result from previous publications and

an estimate of the total alcohol consumption in 2010 for each country considered.

The authors then calculate the “population attributable fraction” for cancer cases with respect to alcohol consumption, which is given by:

While this equation may seem sophisticated, in practice, integrals reduce to sums, so essentially this just boils down to performing some additions and multiplications in a table that combines information from three different sources. At first, note that this “strong evidence” does not correspond to results from randomized control trials, nor from cohort studies, but merely from a statistical analysis of data on country-level alcohol consumption. While the original paper does provide uncertainty estimates, the authors only account for uncertainty propagation in the estimate, not for uncertainty in the data used. In this case, country-level alcohol consumption is a very imprecise data source, which even the authors acknowledge, as for instance, it is hard to distinguish domestic consumption from consumption generated by tourism. Moreover, the procentual estimates of cancer cases are based on the explicit assumption that cases occur exactly ten years after alcohol consumption, which is as arbitrary as it gets. Based on all the above, the publication by Rumgay et al. should be seen as an indication that may merit further investigation, but definitely not as hard evidence to base public policy upon.

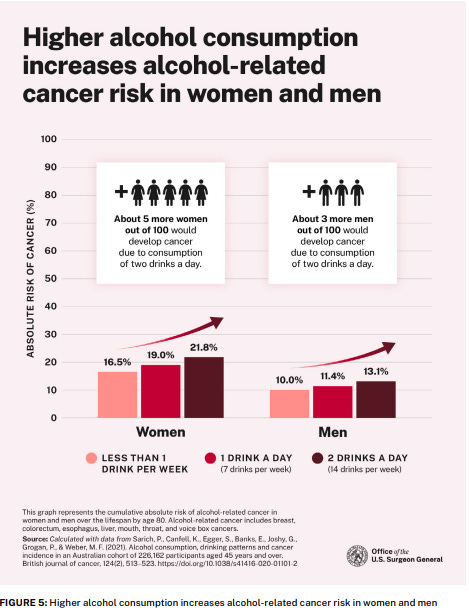

To be clear, the US Surgeon General’s Alcohol Advisory cites more than one publication. But Rumgay et al. is the one most prominently presented, which is telling. However, it is not the only one that merits investigation. In Figure 5 of the Advisory, the proportional increase of cancer risk with respect to alcohol consumption is plotted. The numbers shown there are “calculated with data from a publication by Sarich et al. in the British Journal of Cancer.” The first question that comes to mind is why the Surgeon General blindly copies the results from Rumgay et al., yet only uses the data from Sarich et al., to then apply slightly different formulae to them.

That left aside, the paper by Sarich et al. is worth a deeper dive too. As it turns out, it is an observational study based on 226,162 Australian participants over a period of five years. The study records drinking habits reported by the participants as well as cancer cases and then builds what is called a “Cox proportional hazards regression model” to relate cancer incidence to drinking patterns. It isn’t all that clear why the previous study assumed a fixed lag of ten years between alcohol consumption and cancer emergence, but in this study, any cancer reported over the course of these five years is counted and related to reported drinking patterns. Note that there is no guarantee that the individual cancer cases included are due to alcohol, but the subsumed relationship between alcohol consumption and cancer is investigated at the population level. I would argue that this publication presents rather weak evidence, since many other environmental factors or lifestyle habits may have contributed to each cancer case, which is not investigated.

That remark seems to hold in general for the research that links alcohol to cancer, since this publication states that

“The strongest evidence for the link between alcohol and cancer has come predominantly from observational studies that compared drinking and non-drinking cohorts and/or dose–response relationships.”

I can only observe that in different contexts, the “health authorities” readily discard such studies. For instance, when hydroxychloroquine and a year later, ivermectin, were put forward as treatments for COVID-19, health authorities were all too keen to reject observational studies as “low quality evidence.” Yet in the case of alcohol, they are cited as “strong evidence” and their conclusions are presented at face value.

As stated earlier, there definitely is strong evidence to discourage massive alcohol consumption and binge drinking and this article by no means concludes that we should all drink à gogo. The strength of that evidence wanes, though, as more moderate amounts of consumption are considered. I’m sorry to say, but neither the Surgeon General’s advisory, nor the high profile publications cited therein provide compelling reasons to discourage moderate consumption, less so to print cancer warnings on wine bottles. Even if there were compelling evidence, then it would still be an open question if cancer warnings on labels actually would reduce consumption. Much research exists that points to the contrary.

Besides cancer warnings on wine bottles being both hideous and ineffective, another question that arises is: “Why exactly is alcohol being singled out?” For instance, we know that consumption of high amounts of sugar leads to Type II diabetes and I would not be surprised to find it also linked to cancer if we ran the same statistical analyses as were run for alcohol. Yet we don’t see any warnings on coke.

Besides sugar, just a week ago, the US Food and Drug Administration banned the use of food colorant “Red 3” because … it causes cancer (and is a neurotoxin). Red 3, which had been banned in many other countries for this reason for decades, can still be used as a food additive in the US until January 2027. Among other uses, Red 3 gives Maraschino cherries in cocktails their unnatural red glow. In spite of the known link between Red 3 and cancer, I don’t see a warning from the Surgeon General on tins of Maraschino cherries.

Red 3 may now have been banned, but it is by far not the only food additive with known links to cancer. A scientific review paper lists links between artificial food colorants and negative health outcomes, such as Allura Red being linked to cancers, Citrus Red 2 being linked to lung cancer, “Fast Green FCF” to bladder cancer and indigo carmine to brain cancer. All of these additives are still in widespread use in the US and there are no warnings from the Surgeon General on products that contain them. Likewise, in the US, bread and cereal manufacturers may use potassium bromate to rise their breads faster and azodicarbonamide to generate bread that has a homogeneous bubble structure (and therefore, contains more air by volume). Potassium bromate has been shown to cause thyroid cancer and azodicarbamide causes cancer too when heated, which is of curse exactly what happens when baking bread. Both are banned in the UK, EU and China as a food additive, but not so in the US. Nor do I see a cancer warning from the Surgeon General on breads that contain either additive.

If the “health authorities” and the US Surgeon General in particular, had any concern for public health, they would have taken action action against these food additives long ago. Instead, many of these additives remain in widespread use and they do not care for providing the general public with cancer warnings. In some other areas, “health authorities” even seem to be committed to disparage healthy lifestyles. San Francisco’s health department recently hired an “Expert on Weight-Based Discrimination,” who publicly stated that “you have the right to remain fat.” Quite questionable a statement to be made by a health authority, I say. Obesity can cause a long list of negative health outcomes, such as diabetes, cardiovascular and opthalmologic problems, but it also … is a risk factor for cancer. In spite of all these risks, we see “health authorities” promote obesity rather than disparage it.

Given the “health authorities’” inaction, casu quo encouragement, of other cancer risk factors, the question I want answered is why exactly they have decided to single out alcohol. We can only conjecture, but here is my theory. The United Nations’ “Sustainable Development” Goals have little do with sustainability, but everything with total control of the populace by “elites.” They entail measures like the implementation of a carbon credit accounting system that only serves to further enrich the ultra-wealthy, while imposing a tax on every transaction ordinary citizens make. Because such measures cannot stand up to even the lowest level of common sense, they can only be implemented through harsh censorship. We have all been observing the debauched government efforts to censor “misinformation and disinformation” online.

However, governments will never be able to control physical speech from person to person. As it happens, alcohol is a social lubricant, which makes people more relaxed. People speak their minds with fewer restraints when they have drunk some alcohol. Moreover, they do so in venues where they mingle with strangers, such as bars and festivals, which is very dangerous from a censor’s perspective. It is well known that the word of Enlightenment and civil liberties spread through the British Isles above all through cafés, inns and pubs, because those are the places where people feel relaxed to express their opinions and spread new ideas. The establishment has been trying to shut this sector of the economy down, be it through COVID lockdowns, by demonizing alcohol or by making regulations too burthensome for bars to remain in business. As all of those actions have still turned out insufficient to kill dialogue in hospitality venues, totalitarians like the United Kingdom’s Starmer government plan to introduce “banter bouncer” laws that directly restrict speech in such venues.

However, we are presently in times of change. We can see the internet censorship nonsense gradually be abolished and rest assured, banter bouncer laws will not stand for long, if at all.

I am a good pony. I always rejoice when the beer barrel is filled. I also love my apples, even when they’re starting to ferment. I often get those from our ranchers. They think the apples are no longer good, but hey, I will gobble them up and guess what … there’s some alcohol in them. I know which food is good and natural, I don’t need the Surgeon General to tell me. I will still drink my beer, even when the barrel is marked with toxic, corrosive and carcinogenic labels and when it contains a “health” warning from the Surgeon General. My parents and grandparents drank it quite often and they lived to very respectable ages. So will I. Beer for the horses!

According to a recent Gallup poll, public sentiment on alcohol has shifted. Over 50% of Americans now consider moderate alcohol consumption to be dangerous for their health. This number was only around 25% less than ten years ago. Apparently, younger Americans are in the lead but older Americans are "catching up to the shifted scientific consensus."

https://apnews.com/article/drinking-alcohol-beer-wine-liquor-poll-health-091aa28c3375d30d728d48c628a9023a

Either this poll is unreliable propaganda, or it indicates that Americans are falling for propaganda, which would be more worrisome. According to a recent Gallup poll, public sentiment on alcohol has shifted. Over 50% of Americans now consider moderate alcohol consumption detrimental to their health.

The recent "shift in scientific consensus" about health hazards derived from moderate drinking is based on "science" as solid as the one that "shifted the consensus" to determine that modRNA injections are "safe and effective" and "need to be recommended to the entire population."

The "science underpinning" the health hazards of moderate alcohol consumption is based on flawed assumptions, cherry-picked "evidence" and biased data analysis, as I outlined both here and in my older post:

https://www.wildhorsewisdom.xyz/p/beer-for-the-horses?r=31a4ti&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

We do not need any revised health recommendations on alcohol consumption and I am strongly urging Sec. Kennedy to conduct a thorough review of the recently "shifted consensus," similar to what he is conducting on other topics.

Finally, I can only question why the media are trying to (succeeding at?) convincing us not to drink, but are not doing the same at all for other substances with health hazards, such as marijuana. It seems that one can observe the following trend: substances that may have serious health hazards, yet make the populace lazy, fat, uncommunicative and atomized, are not highlighted in the media. However, those substances that work as a social glue, make people talkative, joyful and speak their minds, are being demonized.

With methodology similar to the one that assesses the global 'alcohol attributable' cancer burthen, here is a publication that estimates the global burthen of type II diabetes and cardiovascular diseases attributable to sugar sweetened beverages.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03345-4#Sec9

Questions can be asked about the methods used in each publication. However, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in most developed countries, outpacing cancer (in general, more significantly so those types of cancer mentioned to be alcohol related). I do not see calls for a warning from the Surgeon General on sugar sweetened beverages for diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk, so why exactly do we urgently 'need' one on alcohol containers?