I trust pear preview

much better than peer-review

Jackie, Bob’s wife, pulled up to the porch of our ranch house. Her daughter Cat was planting some annuals in the flower bed. I was standing right behind the fence, a few yards away, but I could perfectly hear everything they said. Jackie was upset. I saw right away that she had been sulking on something when she was driving back.

“It’s become a drag to go to town,” Jackie said, “those stupid ‘protesters’ were at it again. A bunch of purple-haired lost souls shouting the most insane things. But you know what I found most concerning?”

She looked over at Cat, who guessed “Did they want to abolish tractors to help Palestine save the Donbass?”

“No, not this time at least,” Jackie replied. A few seconds later, she asked: “Do you remember when there was that bloated horse at Four Diamonds, for which they got a visit from animal control?”

“Of course I do,” replied Cat, “who could ever forget that poor animal?”

“Well, the ‘protesters’ want to make bloating horses mandatory”.

At this point, I got anxious too … I know what is good for me and taking anti-petulance drugs is not so at all. I had no time to ponder, though, as Jackie continued her story. “I engaged in a discussion with them, which I maybe should not have… They’re all insane anyways, some of them even pretend to be a cat and wear a carnival costume. But what they said is that we ranchers are ‘destroying the planet’ by having horses and cattle and that there are ‘peer-reviewed publications’ that prove that bloating horses is what we have to do to avoid a ‘climate catastrophe.’”

Cat looked confused, and asked: “And that is true only because it’s in some sort of article?”

The COVID pandemic has brought renewed attention to the importance of the peer-review process in scientific publication. In the early days of the pandemic, guidelines for journalists could be found online that were advising, if not instructing them, only to cite information from sources that had passed peer-review. Academic elites, then and now, will stress the importance of the peer-review process. They effectively project a perception in which the peer-review process is seen as a criterion for trustworthiness. Academic metrics, such as the impact factor (IF) of the journal in which the article has appeared, can further add to perceived credibility. Many academics will posit confidently that if an article has appeared in final print in an academic journal like Science, Nature, or The Lancet, its conclusions can be trusted. In spite of academia’s attitude that ascribes superiority to information that has been published according to their own established processes, even before the pandemic, far from all peer-reviewed publications were reproducible, nor trustworthy. Far fewer are since. Over-reliance on the merits of the academic publication process has cascaded down into distorted media representation of the facts and, eventually, biased public opinion.

To grasp why the peer-review process may not be as watertight as many believe and the media project it to be, let’s dig into how the process works in practice. When a manuscript is submitted, it lands on a journal editor’s desk. The editor is typically an academic professional knowledgeable in the field, who has the discretion to subject the article to actual peer-review, or to reject it. The role of the editor should therefore not be underestimated, since editors can and will often reject a majority of the submissions. Which criteria they use thereunto, is entirely opaque. They can perfectly reject a manuscript because they don’t like the authors, the topic or the conclusions, all of which have little to do with scientific integrity. In practice, therefore, the chances for a manuscript to be forwarded to reviewers increase drastically if at least one of the authors is on good terms with the editor. Academic publishing thusly pretty often acts akin to a country club of fellow academics who meet each other at a set of conferences in the field and is difficult to penetrate for outsiders.

Editorial review is the first hurdle to pass. If positive, the manuscript is then forwarded to a set of supposedly objective reviewers. Most often two or three reviewers will be asked to read the manuscript, comment on it and if applicable, request modifications. It should be noted that this step of the peer-review process is rarely anonymous: most journals will actually share the authors’ name(s) and affiliations with the reviewers. Reviewers will submit their findings, based upon which the authors shall revise the manuscript until reviewers have no further objections. This step too is prone to ample subjectivity: reviewers can write a positive report because they like the authors, the conclusions, or even because they accepted to review, but lack the time to do it properly and then just write a report with a minimal set of remarks. Conversely, reviewers can write a nasty report if they don’t like the authors, their institution, the topic or conclusions, or if they happen to be working on a similar topic themselves and want to publish their own work first. All of these motivations are supposed not to occur if everyone acts with scientific integrity, but unfortunately they are quite common, also in elite academia.

(If you think Wild Horse Wisdom acts with scientific integrity, please consider to subscribe. We have a free tier.)

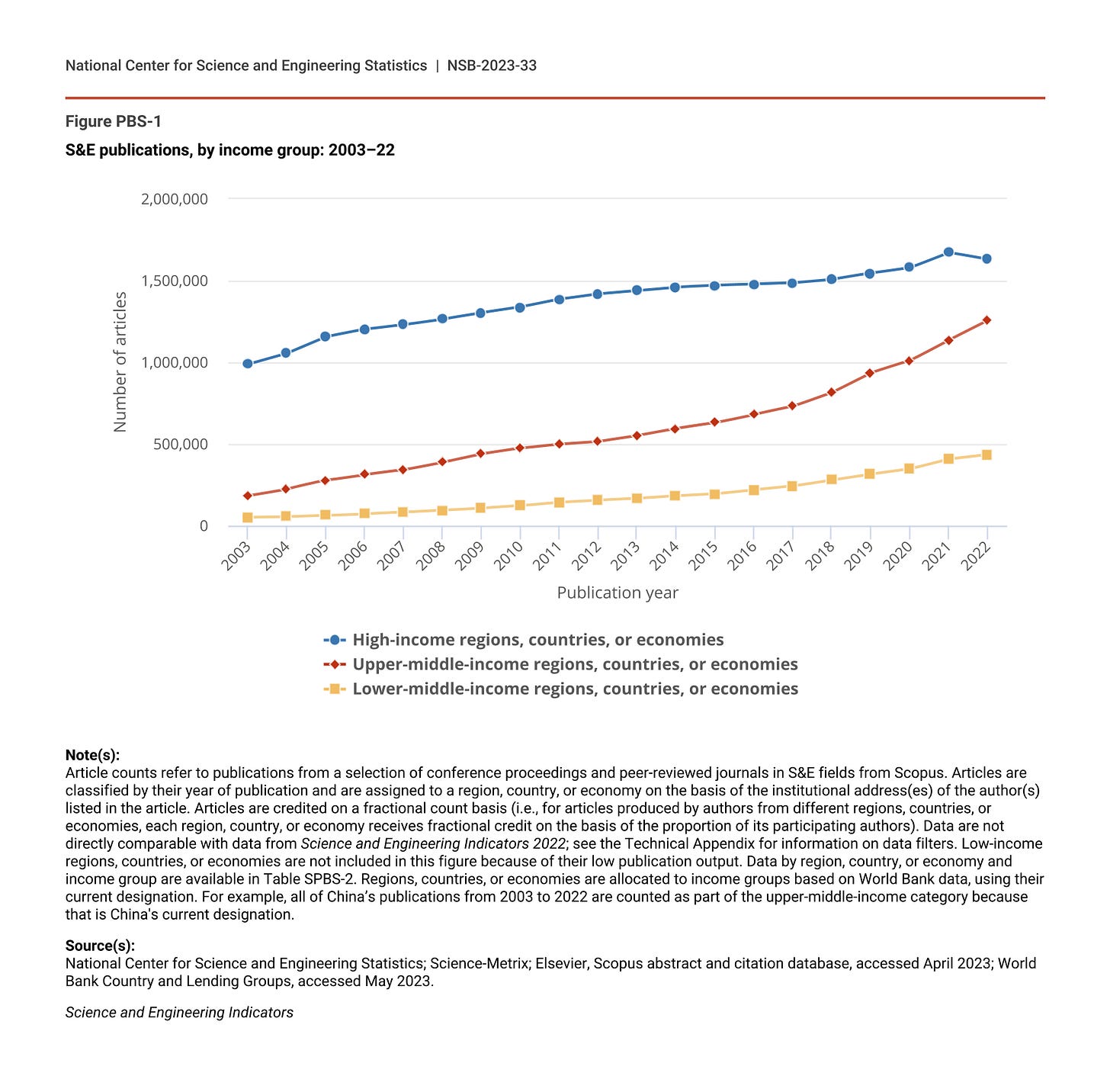

The main side effect of the flaws in the peer-review process is that many rather low quality articles get published. The volume of scientific papers published has more than doubled over the last twenty years. In the science and engineering fields alone, over three million articles appear every year. With those volumes of material processed, it is understandable that not all papers are reviewed with the diligence due to guarantee reproducible science.

The statement that much scientific work was not reproducible, was already true in the early 2000s. This is underscored most of all by Stanford professor Ioannidis’ paper “Why most published research findings are false.” Researchers who set off on a new project, will need to review the existing literature. In line with Ionnadis’ paper, in the research community it has been known for decades that researchers need to evaluate the papers in the existing literature critically and filter out the academic junk. They should by no means accept all results of all papers at face value, even though all of them have passed peer-review. Neither should we.

The effect of low quality research that passes peer-review is largely benign: one may think of it as giant printing press of scientific spam. However, things are different when the results published without too much care start having an impact on our lives. Let’s recall that prof. Ioannidis’ paper mentions results from the medical sciences. What happens when doctors prescribe medicine based on results that should never have passed peer-review and subject patients to unnecessary harm? Or even worse, when those irreproducible results become the ‘standard of care’? Who thinks that such could never happen, needs to reconsider. It seems that this is exactly what has happened in quite a few cases. For instance, since a few years, the “standard of care” to “treat” children with so-called “gender dysphoria” has become to subject them to hormone treatments and drugs that previously used to be referred to as “chemical castration” and “gender affirmative” surgeries that can much more truthfully be described as “genital lobotomies.”

How did we get there? Well, because peer-reviewed papers exist, mainly published in the journal of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), that claim that prescribing these barbaric “treatments” will prevent the subjected children from committing suicide. We all know that children did not collectively commit suicide prior to 2020, not did youth suicide numbers drop significantly since. So how did this work get peer-reviewed and published? The answer is simple: because WPATH is not a society that professes the scientific method, but rather a pseudo-scientific propaganda clan. If the publishing society is a group of people who are ideologically captured, then so are the editors and the reviewers. In fact, in that case, reviewers will not check scientific accuracy, but rather adherence to the preferred narrative. Since the release of the leaked WPATH files, it has become clear that even at the most senior levels of WPATH, serious doubts existed about their own messaging. It is clear what needs to be done on this topic. It is time to ban any “gender-affirming” castrations and lobotomies and to start teaching children that their bodies are good the way they are, because the universe knows and has always known how to put creatures on the planet in the right body.

WPATH’s pseudo-scientific practices are a good example of biased narrative promulgation, but they are by no means the only society that does so. We can detect similar dubious practices across the scientific spectrum, in the most “respected” venues and by authors considered by many to be “the best of the best,” such as Ivy League scholars. One example is the paper entitled “The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2,” which appeared in Nature Medicine on March 17, 2020, a time when there were still many open questions regarding the then-novel coronavirus. The proximal origins paper concluded shamelessly that the virus’s only plausible origins were natural zoonotic transmission. At the time the paper was published, it was already clear that the furin cleavage site in the virus corresponded one-on-one to previously published results on gain-of-function research. It was also clear that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was very close to the site where the virus outbreak was assumed to have started. Moreover, it was exceedingly unlikely that natural zoonotic transmission would have occurred in Wuhan to humans from bats whose natural habitat are caves hundreds of miles to the south of that city. For all those reasons, the “proximal origin” manuscript should not even have passed editorial review, let alone peer-review. Yet it did. Moreover, we meanwhile know from Freedom of Information Act requests, that the first author had pointed out that the virus pretty much appeared to be the result of a lab experiment rather than of zoonotic transmission until shortly before the article appeared.

(If you agree that pony common sense can be transmmitted zoonotically, please consider to subscribe. There is a free tier.)

One may conjecture that the pandemic was an extreme set of circumstances that made certain scientists lose their usual cool-headedness. Yet we can still observe dubious publication practices today. Just a few weeks ago, an article has appeared in Nature, that claims that economic losses from climate change can be attributed to emissions from individual oil companies. It even comes up with a estimate for Chevron in the abstract: between US $791 billion and $3.6 trillion and boldly states that “the scientific case for climate liability is closed.” Real climate scientists know that climate attribution is pseudo-science, created by certain interest groups to target industries they don’t like. Climate “attribution” exercises are constructed to arrive at predetermined conclusions, which is only possible by starting off from a set of flawed assumptions. This paper is no different. It assumes that (i) the global south has suffered economic damages due to ‘extreme heat,’ (of which there is little evidence) (ii) that those heat related weather events are due to climate change (may be partially true), (iii) that climate change is due to anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions (completely ignoring other, more likely, causes like solar activity) and that carbon emissions can be traced back to individual oil companies (maybe partially true). Moreover, it evaluates the links between each of these steps quantitatively by using models and assuming those models to be accurate (rarely a good assumption). Since this paper is based on extremely shaky, unproven foundations, it should not even have passed editorial review. Yet it appeared in Nature, an “authoritative source,” with a very high impact factor (2024: 50.5), where “the best of the best” publish. Both authors are Ivy League scholars indeed. We can thereby observe that neither the publication venue, nor the authors’ affiliation guarantees high-quality results.

One pernicious effect of peer-review is that it has allowed much harmful junk “research” to get published, such as the “results” mentioned before. However, a possibly equally destructive effect can be observed when high quality research does not manage to get published. Imagine being a great medical researcher who runs a large scale observational study on “gender-affirming care” and arrives at the conclusion that the number of suicides actually increases in the group that receives those treatments. Will WPATH consider that article for publication? Likewise, given that Nature just published the pseudo-scientific paper on climate “attribution,” will it accept a paper that claims that there is no link between carbon dioxide and economic losses due to heat waves?

Things can even get more extreme than an article not being able to pass peer review. Sometimes, journal editors and referees thankfully still act with integrity, which then leads to papers appearing that do not align with political expectations. In the old days, that would be the end of it. Nowadays, though, there is another solution: retraction. We already discussed the course of events regarding the Alimonti et al. paper, that merely states facts aligned with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change well known to climate scientists “in the know,” such as there being no observable trend in the number, nor the intensity, of tropical storms. That paper passed peer-review, was published, and then retracted when a journalist (read: not a scientist) from Agence France Presse generated outcry and got the publishing house to retract it.

Likewise, at the height of the COVID vaccination frenzy, Dr. Peter McCullough, who is one of the world’s leading cardiologists and most published scientists in the field, noted heart related issues that could most plausibly only be ascribed to administration of the modRNA vaccines. He teamed up with Jessica Rose, a leading microbiologist and statistician at Stanford University. The two scientists meticulously documented their findings and submitted a paper that associated the modRNA vaccines with the side effect of myocarditis, a side-effect that many health authorities meanwhile recognize. The paper passed peer-review and appeared … only to find itself withdrawn by publisher Elsevier without explanation a little later. While these papers were removed, we note that the “proximal origins” paper still has not been retracted, in spite of its lack of scientific accuracy and the known conflicts of interest.

The examples cited are all individual cases, but a trend can be discerned. While some thorough science certainly still appears, there is a growing list of topics in which proper use of the scientific method has become verboten. Instead, the scientific literature in those fields seems to have morphed into propaganda printed in the page layout of a scientific journal, such that it appears “authoritative.” Recent polls show that the scientific community has lost trust with the general public. Based on the above, one can only say that to be the case for good reasons. If the scientific community wants to regain trust, it will have to start to rigorously enforce the scientific method and make sure that results published in the most respected venues are all reproducible.

Some of the most “authoritative” sources are readily publishing junk, while rejecting or withdrawing sound science. That may be scary by itself, but it is all the more so if those results are used to train artificial intelligence models. Most of the AI models available to the general public will be trained to assign a higher weight to what their creators label as “trustworthy.” That may merely be a nuisance if we only use them to get answers, in which case we can learn to look elsewhere. The situation changes, though, when such models are used to make decisions for us. Imagine, for example, a model censors us if we dare to say that extreme weather events cannot be “attributed” to carbon dioxide. Or even worse, a model that will decide whether or not to give credit based on narrative adherence.

Such practices need to be outlawed straight, but as we speak, they are not yet. On the contrary, some ghost concepts still seem to be gaining traction. For instance, accompanied by the bold statement that “AI is the future,” the New York City Subway is rolling out AI technology to analyze people’s behaviours. Sweaty palms, pacing around or shifting one’s weight too often balance could all lead to being flagged as a “pre-criminal” and may trigger a police team to be dispatched. This technology resides in the pseudo-scientific knowledge of “pre-crime,” which is based on models that associate certain behaviours with crime at a later point.

A decade ago, deployment of such tools was decried as building “weapons of math destruction,” but it seems that we haven’t learnt too much since. I’m sure that one can find some peer-reviewed paper that associates the number of times one shifts one’s weight balance to any sort of crime, but as we have seen before, the mere fact that it has been peer-reviewed does not mean that we should believe it. More less so that we should build models on it that have an impact in the real world. In fact, we should write legislation to outlaw such practices.

I trust that we can turn the tide around and ride the wave of the return to reason, also here on the Ranch. We have pretty good grips on reality over here. I don’t really need peer-review to discern truth from lies. Maybe that’s because I’m a horse: I can rely on my pony common sense. Here’s what I care for instead: pear preview. I can’t wait till those succulent, ripe pears start falling from our tree!

Public News reported that "renowned" IPCC scientists are pushing to get a thorough study that established that sea level rise is not accelerating retracted. They are well aware that their own conclusions do not align with on-shore measurements. Instead of doing real science and investigating why their own models do not match reality, they want to silence those who pursue the truth.

https://www.public.news/p/top-scientists-deliberately-misrepresented

If retraction happens, this will be another sordid example of a retraction for no justifiable reason by immoral "authoritative" voices. It will be yet another shining example of why the academic establishment is failing us over again and another reason for distrust in academic publishing, above all so the "most reputable" venues.

We horses are astute observers, but we are not the only creatures who notice that peer-review has devolved into anything but quality control. Here is an excellent piece on the same topic:

https://wherearethenumbers.substack.com/p/can-we-trust-independent-peer-review?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=1229032&post_id=163633978&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=uhcpo&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email