The social cost of ranching

... can only be negative.

Rancher Fred from Triple Z Bar stopped by last weekend, as Bob was putting some steaks into the smoker. He was upset. At first, the situation seemed deplorable, yet not unusual. “I got a notice from the Revenue Agency,” he said.

Well, we’ve all owed some taxes from time to time, haven’t we? The most important piece of information still had to drop, though. “My tax rates are doubling, to account for the ‘social cost of ranching.’” He started to weep, as he added “I’m sure you’ll get such a notice too, Bob …” None of us knew what to make of it, but maybe Cowboy Jake found the best way to put it, as he said: “I thought producing meat was a social service, not a cost?!”

Regardless of where you are in the West, you are not in a region that taxes a “social cost of ranching.” Yet. But also regardless of location, you are not far from having such a tax either. For the last decade, academics and governments alike have been trying to estimate the so-called “social cost” of greenhouse gases. A separate estimate is produced for each greenhouse gas, which can then be used ad libitum to account for the “social cost” of any economic activity, including ranching, through the manipulations of capricious and arbitrary “carbon accounting.”

So what exactly is a “social cost” supposed to represent? Using the example of carbon dioxide, according to a 2017 statement from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the

The SC-CO2, is a measure, in dollars, of the long-term damage done by a ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in a given year.

Herein, the “SC-CO2” is commonly referred to as the social cost of carbon. Let’s first pause at the above definition and note that it assumes that any additional tonne of emitted carbon dioxide will cause long term damage. That seems a shaky assumption at best. However, scientists and administrators involved in work on the social cost of carbon have long moved on from asking questions about the basic rationale of their work. Rather than having truly philosophical or scientific discussions, they will have endless debates on how it can best be estimated.

To arrive at an estimate, we need to bear in mind that the social cost of carbon should represent the discounted price of cumulative damage occurred in the future owed to an additional tonne of carbon dioxide emitted right now. Of course, that estimate will depend on the time window selected. But even if we can agree upon a time window, the key question to answer is how we can ever reliably estimate economic damage far into the future that is attributable to present emissions.

In practice, two routes are taken. The first is to use so-called “integrated assessment models” (IAMs), which combine climate models with economic models to obtain a dollar value. A second option consists of using the economic damage estimated from past meteorological disasters and partially attribute that cost to carbon emissions, which can then also be forecast into the future. Each of these routes are based on further sets of assumptions and outright options, such as which climate and economic models to pick, or how to statistically analyze past events.

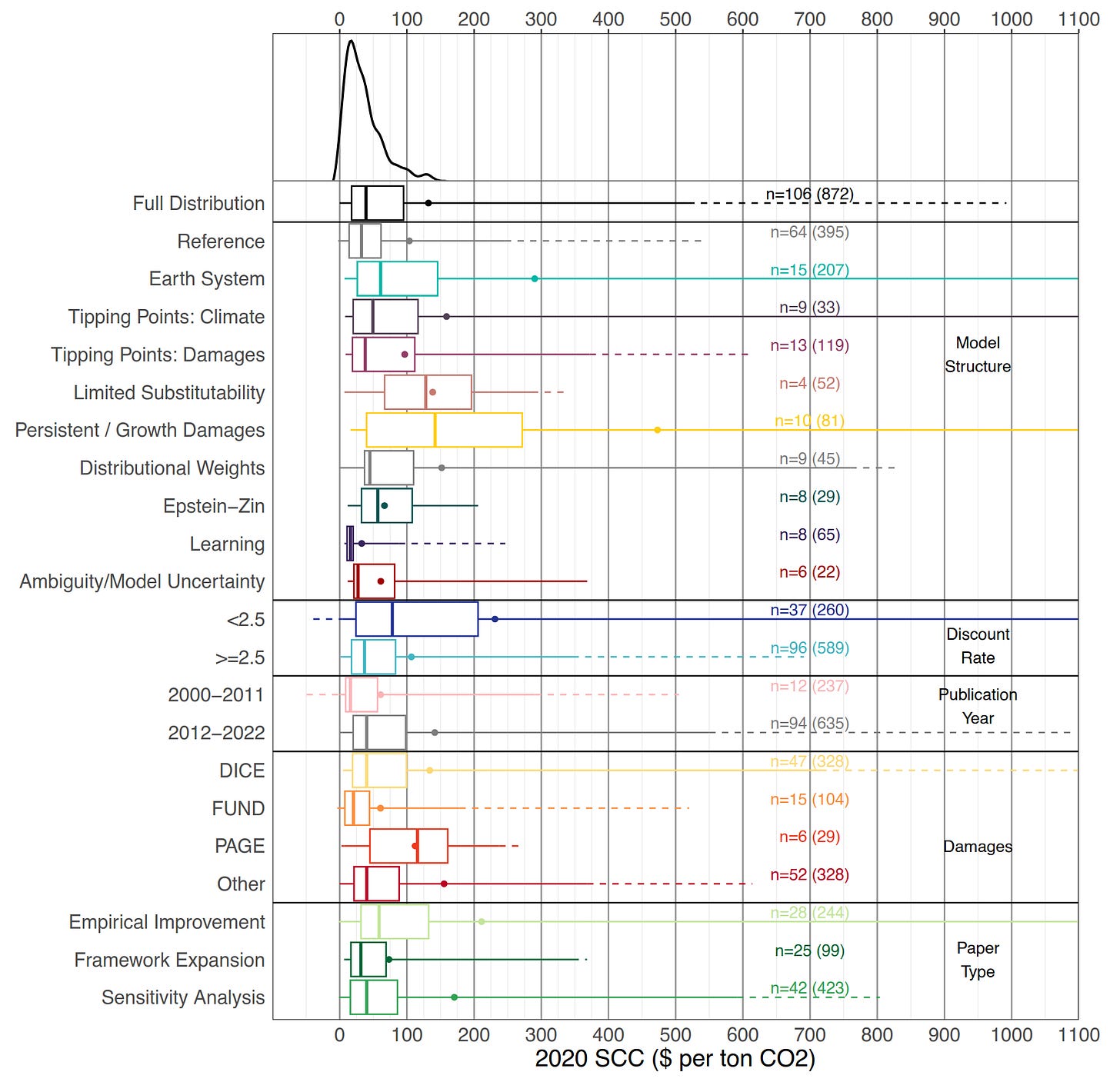

For all of these reasons, we should not be surprised to learn that many different approaches exist. Each of the approaches to model the SC-CO2 yields a different estimate and they differ by wide margins. Several academic papers even report the results from sundry different methods or options at once. To help us see the trees in the forest, a recent paper by authors from the US National Bureau of Economic Research has attempted to shed some light on the differences between the estimates. The authors aggregate results from … no less than 1823 estimates of the social cost of carbon, which they have obtained from 147 different studies. Individual estimates range all the way from negative values to 1100$/t CO2. The authors expand upon the drivers of such a big variance in the results. Howbeit, we will not dive deeper into the underlying causes of the differences between the estimates. The one message to take home is that there is in fact an immense range of results, all of which have been derived by scientifically acceptable modeling techniques.

Given that there is such a wide variation in the numbers, it inevitably becomes very challenging to base any sort of policymaking on the social cost of carbon (or other greenhouse gases). Yet the latter is what many politicians of different stripes in many countries are doing. Notably, many of them make claims that they are “following the science.”

Even in the United States, no administration seems to be immune from touching the subject of the social cost of carbon. Per our records, the concept of embedding the SC-CO2 into policymaking was introduced by the Obama administration. They first announced to have “established” an SC-CO2 of $37/t. In 2017, the incoming Trump administration lowered the estimate to $7/t, yet stopped short from eliminating the SC-CO2 altogether. Fast forward by four years, the Biden administration increased the official SC-CO2 to $51/t. Only two years later, in late 2023, the Biden EPA updated the estimate to $190/t, to adapt to “the latest science.”

Given the wide variation in the academic results cited above, de facto, any of the official figures can be deemed “scientific,” be it the $7/t, $190/t or anything in between, since for each of those, publications exist that support them. Based on the meta-analysis cited above, some of these results can be deemed “more likely” than others, but none are “unscientific.” However, instead of weeding out the differences between the results, let’s revert to what these models represent and ask if we need them in the first place.

Integrated Assessment Models to establish the social cost of carbon combine economic models with climate models. Each of these classes of models adhere individually to George Box’s aphorism that “all models are wrong, but some are useful.” Moreover, in this context, it is also a good question how useful some of these models really are. On the econometric side, economic models can have utility in the short term, or slightly farther out in case economies develop in a mode of relative stability. However, not a single such model has been able to predict any economic shock, such as the dot-com bubble, the 2008 leveraged mortgage crisis, or the COVID pandemic. Macroeconomic models are neither capable to forecast economies fifty years into the future, nor are they designed to do so. That greatly jeopardizes their usefulness as a plugin into IAMs.

If the economic side of IAMs is already shaky, then the climate side is even more so. Climate models typically plugged into IAMs will start from the axiom that additional carbon dioxide emissions will have detrimental effects on climate in the future. However, that is not guaranteed at all. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration is by no means the sole lever that impacts climate. According to some publications, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration lags temperature. If true, CO2 would rather be a consequence of warming temperatures than a cause. However, even if it is a cause, it is not the only one. Solar storms, cosmic radiation, volcanic eruptions and many other factors contribute to climate. These are factors that are typically not well represented in IAM climate models, if at all. Moreover, climate models in IAMs are based on assumptions of acceleration of hurricane frequency or intensity, on rapidly accelerated sea level rise, or increased frequency of other catastrophes. Unfortunately, all of those catastrophes are so far only present in climate models, since no increase in actual activity can be measured. They may well turn out to be artifacts of climate models, rather then real phenomena. Yet the economic damages in IAMs are exactly those that form the basis of the “social cost of carbon” calculations.

(We have a free tier, so subscribing does not need to cause you economic damage)

The SC-CO2 is derived from highly uncertain forecasts from a set of models, the accuracy of which can be questioned on their turn. It seems to be an economic version of a common flaw seen in recent years in policymaking that claims to be “based on science:” it uses forecasts into the future from models that fail to accurately predict the present, which is in fact a highly unscientific practice. Moreover, to represent the result as a precise number is very deceptive to the general public. Instead of claiming that the SC-CO2 “is” $38/t “according to the latest science,” a more truthful message would be that “it has been estimated to be between -15 and 1100$/t.” It is an open question which fraction of the population would support changes to their lifestyles based on the latter communication.

The second Trump administration has recently abolished the use of the SC-CO2 altogether, for good reasons. Other Western countries must follow their lead. Meanwhile, we even see the academic establishment gradually wake up. While they don’t question the validity of as many aspects of IAMs as we have here, a recent publication from Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy states that:

“But the truth is that meaningful estimates of all the ways today’s emissions will affect the world decades and centuries from now are impossible.”

and arrives at the conclusion that:

“While reducing greenhouse gas emissions can prevent huge risks to public health, economies, and ecosystems, these benefits cannot be meaningfully captured in monetary terms, as the SCC purports to do.”

We do not seem to be the only ones who do not see any practical use for social cost of carbon estimates. However, we can only observe that massive resources have been poured into estimating that same useless metric. Hundreds of studies were commissioned that fed into at least as many SC-CO2 estimates. Many of those studies were funded by Western governments. That leaves us to wonder why such a frenzy even started in the first place. It seems pretty straightforward to us that it is impossible to obtain an accurate estimate of the social cost of carbon, nor is there a compelling motivation to even try to estimate one. So why can’t we focus our attention on issues that really improve peoples’ lives?

The social cost of carbon saga, which is now coming to an end, is merely a reflection of the soullessness of certain Western “elites.” Their lack of true religion has fostered a panoply of deluded ideals, which they see as existential necessities and pursue as idols: to “prevent” pediatric suicide, we “must” sterilize and mutilate children, which will make them “happier.” Sure. We also “need” to “lock society down harder” next time a new pathogen appears, because the 2020 lockdown was only flawed for not having been tight enough, as a recent British government report claims. Sure. And of course, the planet “is burning,” so we need to waste resources on carbon accounting and estimate the social cost of carbon. Resources that could equally be used to help the disenfranchised around the planet, but spending them on useless administration is preferred. Sure.

Each of these societal trends are reflections of the moral bankruptcy that has infested certain (most?) Western “elites.” There is no place on earth where said moral bankruptcy is more complete and institutionalized than in the European Union. The present context is no exception. The EU recently introduced its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which includes a tariff on imports from countries that do not quantify their carbon emissions (note that the US is not the only country that imposes tariffs).

Indeed, European administrators increasingly see themselves as the saviours of the planet, so they have to force their own delusion onto others. It should be clear that if there really were a climate emergency, carbon accounting would do nothing to stop it. In fact, its own existence causes additional emissions by creating a futile administrative burthen. But its effects do not stop there. There are nations that cannot afford to implement all the required administration. Which are those? Of course, the poorest. So a direct effect of Europe’s inverted moral zealotry is that it will make the poorest even poorer. Who has the moral high ground? Brussels based “elites” urgently need to ask themselves that question.

Fortunately, here at the Ranch, we don’t need to ask ourselves such questions. Political activism still works, also for truly good causes. Even more so for those who find the right partners. It turned out that one of the influential proponents of social cost taxation was an owner of a large wind farm around here. With wind already having shaky economics by itself, he would have to close if he had to account for the social cost of wind farming. The incessant flow of spare parts and maintenance crews ended up having a social cost of carbon too.

In a fight like this, it is wise to make as many allies as possible. For once, ranchers and green economy advocates teamed up and social cost taxation was shelved. Hopefully, for once and for all.

A while after the drama about the social cost of carbon was over, Eileen and Madison, two local cowgirls, were riding us. They were already joking when Eileen asked: “What’s the social cost of horseback riding?”

Madison answered swiftly and with a smile: “that it makes you feel too good!”

Social cost of “carbon”, if there in fact is any, is dwarfed by the social benefit …

They pretend to care about humanity, but all they are interested in is their own personal glory and fortune.