We horses can swim

but we don't if we don't have to

We had a long ride in our horse trailer out east last week. We visited one of the very few rodeos they have over there. The ride wasn’t very convenient, but it surely paid off. We learnt quite a few interesting things. One of those was that, apparently, Chincoteague ponies now go for millions a piece in the annual auction. Until just a few years ago, they were considered broncos that just happened to have been born on the beach. No longer so. We started asking around and we soon found out why that is: upmarket horse dressing stables over there now want to have at least one Chincoteague pony in their ranks, so it can teach the other ones to swim. When we acted surprised by that statement, we largely got a stink-eye, oft-accompanied by the one-liner that seemed to explain everything: “Sea levels are rising.” Sometimes, it would get the inevitable epithet “… because of climate change.”

Obvious enough a motivation, isn’t it? Or is it? Well, to answer that question, it is necessary to separate those two statements out and analyze them individually. The general assertion that “sea levels are rising” is definitely not true for all seashores on the planet. For instance, Scandinavia, just like large sections of Canada, was largely covered under a thick sheet of ice during the last ice age. Once the immense pressure from the overhead ice disappeared, the freshly exposed land started rising, and it still does so today. In the scientific literature, that phenomenon is referred to as the post-glacial uplift. The land in Scandinavia rises pretty fast too, at a rate of 1-2 centimetres per year. In Sweden, archaeological finds of medieval ships and marine equipment can be found miles inland, at places that used to be on the seashore less than half a millennium away. The Baltic Sea may once again disappear, or become a set of lakes, as it is believed to have been before the ice age too.

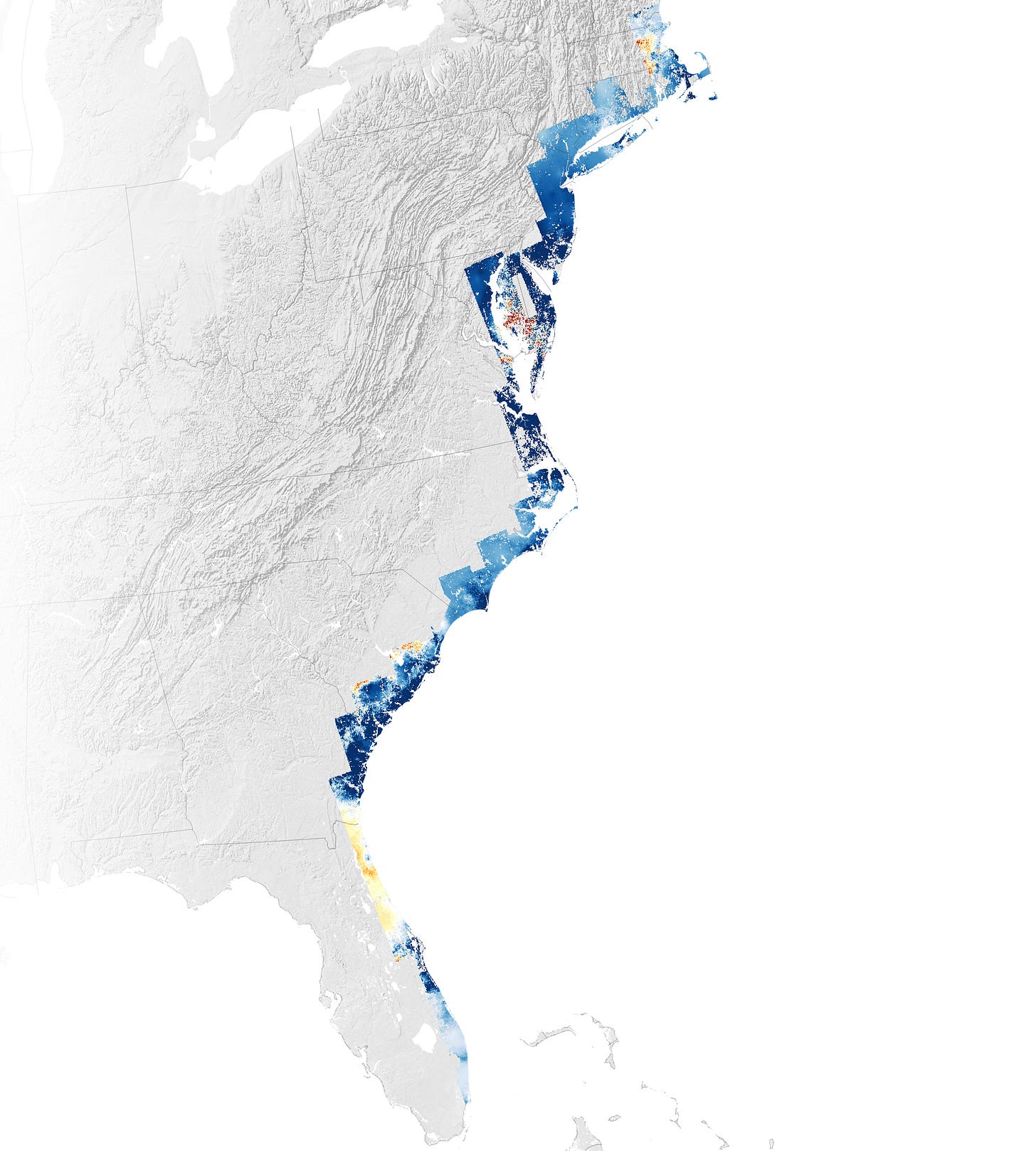

Not all land on the planet can enjoy a post-glacial uplift, though. As opposed to land in Nordic regions, much of our land height is stable and some is sinking. One notable example of sinking land can be found along the US’s Eastern Seaboard, which is known to subside at rate of 2-3 millimetres per year. This phenomenon has been known for decades and can be managed, if the right measures are taken.

Accounting for movements in the land mass, indeed, the stables on the East Coast do have a legitimate concern. If managed properly, though, they will not see any dramatic changes in their lifetime. Or will they? Listening to mainstream media, one may be led to think that most of the planet’s coastal regions will soon flood. That narrative is old and was certainly accelerated by Al Gore’s 2006 movie An Inconvenient Truth, which showed images of the Netherlands disappearing. The movie represents a parabolic depiction of the scientific climate at the time. For instance, back in 2002, scientists made a bold prediction that Kilimanjaro’s snow cap would disappear by 2020. Of course, that did not happen. We note that this is not to be taken as evidence that climate would not be changing. However, it underscores the then-prevalent alarmist mood in scientific circles, which seems to have resuscitated in recent years. The 2017 publication cited before on the land rising in Sweden already ends in a note of caution:

“Although the inhabitants of Finland and Sweden do not have to worry about the effects of sea level rise for now, it is highly likely that will change in the near future.”

One would wonder why they would have to be concerned about floods on a rising landmass? Yet more recent publications strike a generously more alarming tone, also in the case of Sweden. A 2022 Reuters publication claims that a “Viking bastion on uplifted land is now menaced by rising sea levels.” Let’s note that the bastion described therein is … five meters above sea level, on land that keeps rising. Nonetheless, its authors contend that sea level rise is projected to be faster than the land’s, which may lead to the bastion being engulfed by salt water soon. Noticeably, sea level projections from the World Bank show worrisome outcomes too, also for Sweden.

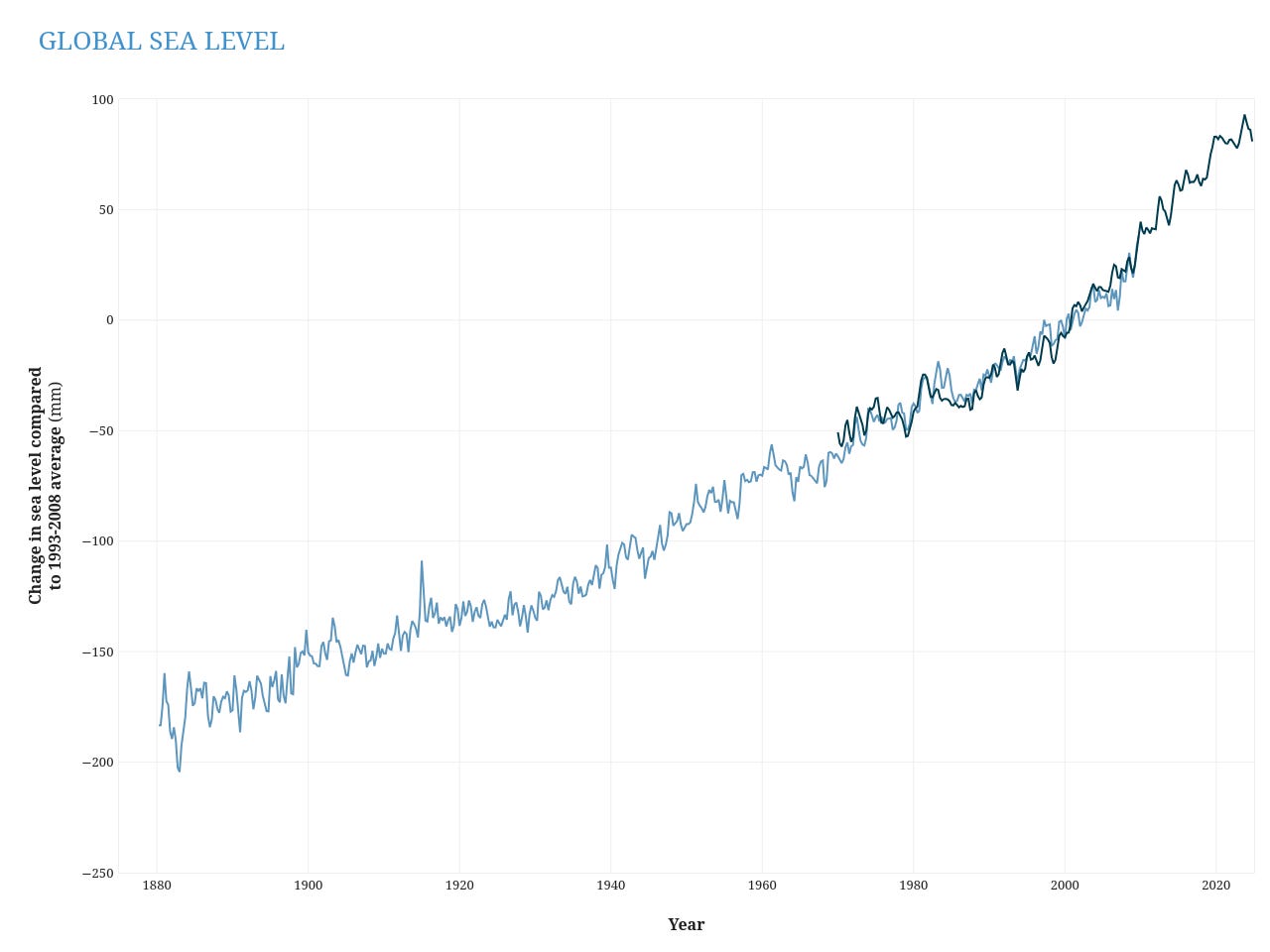

The fact that projections adopted by government bodies, such as the World Bank, arrive at forecasts that seem overly alarming and not in line with on-shore evidence, leaves one to wonder where they come from. In short, the answer is that they are derived from “authoritative sources.” One such source is the United States’ NOAA, which projects an accelerating rate of sea level rise and plots that in a nice chart too. Much of the data in that chart are taken on their turn from the Australian government-funded research body CSIRO. To arrive at the data used by NASA, CSIRO authors Church and White have reconstructed global historical sea levels based on satellite measurements.

While that line of work produces optically appealing results, much can be said about the methods used to arrive at them. Let’s at first note that the curve represents global sea level rise. A global number is by definition a summary of local effects and conclusions drawn on a global level do not translate one on one to local sea levels. Secondly, the sea level data are processed from satellite measurements, which require triangulation that involves two satellites and corrective algorithms. We could write a lengthy post on how those satellite measurements work, along with historical critique against their use. Yet some facts need to be pointed out here. The above chart depicts data that were collected from several generations of both satellite technology and corrective algorithms, which makes the historical data hard to align. Nonetheless, a curve is fit through the data, ignoring their inconsistent origins. The curve so obtained happens to be parabolic, which then supports the statements along the lines of “rapidly accelerating sea levels.”

While projections from global sea level data derived from satellite measurements do support the conclusion of fast-rising sea levels, those projections fail to align with actual measurements on land. At this point, one may be inclined to think that because our technology has improved, concerns about the accuracy of satellite-based sea level measurements are largely a thing of the past. Except, they are not. A 2024 paper by French authors states that:

“But the use of altimetry close to the coast remains a challenge from both a technical and scientific point of view.”

It then expands on discrepancies between on-shore tide gauges and satellite-based altimetry and their root causes. We would argue that, before we start relying exclusively on satellite-based measurements, we should ascertain that they are consistent with accurate on-shore tide gauges. It is therefore highly misleading to project models based on global aggregate sea level measurements obtained from satellites to future observable effects at the shoreline.

Fortunately, we are not the only ones to make that observation. Two Dutch researchers have recently aggregated data from accurate on-shore sea level measurements around the globe. For each of these locations, they have answered the question if a linear model fits the data best, or if a quadratic model applies, as is used in e.g. NOAA’s projections. The answer was quite staggering: almost in every location analyzed, a linear trend fit the data best. In mundane terms, that means that sea levels are still rising in exactly the same way they have been doing since we record them. They are rising, at a slow rate, and are still doing so as a result of the last ice age having ended over ten thousand years ago. No “dramatic acceleration” can be observed from on-shore measurements.

(If you would like a dramatic acceleration of Wild Horse Wisdom posts, please consider to subscribe.)

Since no acceleration is observable, we don’t even need to answer the thorny question if it is “because of climate change.” We note that that could be a reasonable question in this context, which it is not in many other contexts in which it is frequently brought up. For instance, since climate is a slowly-moving thirty-year average of weather, which includes temperatures, climate can never be a cause of changes in temperature. Yet the United Nations present such a Catch-22 statement as a truth: an expected effect of climate change are “hotter temperatures.” However, rising temperatures could increase thermal expansion of ocean water, as well as polar ice melt, and thereby accelerate sea level rise. In theory, that is possible, but accurate on-shore measurements do not support the assumption that it is really happening.

It is hardly a coincidence that the scientists who care (or should we say: dare) to look at this question, are Dutch. The Netherlands have a long history of reclaiming land to the ocean. The country’s lowest point is just shy of being seven meters below sea level. According to Wikipedia, “it is estimated that about 65% of the country would be under water at high tide if it were not for the existence and the country's use of dikes, dunes and pumps.” Reclaiming land to the ocean is so deeply ingrained in Dutch culture that Dutch settlers started doing just that when they arrived both in New York and Cape Town, in spite of having an entire unexplored continent available.

Since the Netherlands are located at very low levels of elevation, it lends itself to be used as an example of a place that would suffer immensely from drastic sea level rise. It is no coincidence that it was brought up in An Inconvenient Truth. A recent Politico article reiterated the question “When will the Netherlands disappear.” The answer to that question should be “we don’t know,” since the Netherlands will disappear if sea levels do rise by a lot, but … there are no actual signs to make us believe that that is about to happen.

Both in the case of predictions for the Netherlands and for Kilimanjaro’s ice caps, along with many other examples, a more accurate summary could be entitled A convenient lie, rather than An inconvenient truth. Convenient to whom? Well, since bodies like the World Bank are endorsing the pseudo-science of rapid sea level acceleration, those who benefit from that assumption being taken serious are those who deliver services to account for “climate risk,” as well as those who want to (ab)use that system to punish industries labeled “the culprit.” Just as we outlined in the context of tropical storms, sea level rise is another area in which there is absolutely no reason to adopt climate or carbon accounting. Likewise, it seems to be yet another area where some models built by “experts” based on flawed assumptions are taken by authorities as more authoritative than actual observations. If authorities really believed in the scientific method, they would only draw conclusions from models that agree with reality.

As it happens, I know A Chincoteague pony. Four clovers has one. He’s an ageing stallion. They bought him years ago, before Chincoteague ponies were à la mode. There usually isn’t much of an advantage to being able to swim in the dry climate over here, but hey, there is a pond on their eastern pasture. The other horses just drink from it, but he will jump in from time to time.

I also heard that some nursery on the outskirts of town has started planting Brazilian rain trees. They say there won’t be any winter this year. The most recent models predict a tropical climate over here, starting in November. When common-sense cowboys ask them the question why we aren’t observing any of that, the answer invariably is: “The science has changed.”

Except, it hasn’t. Even in the context of today’s near-complete politicization of the academic publishing bodies, research has passed peer-review in 2025 to attest to that.