Wild horses surely have free will

and so do humans

Cowboys Jake and Hunter were going to ride Snowflake and myself out into the high pastures. Snowflake is a thirteen hands tall white mare who I get along with very well. As Jake opened the gate net to the stables, I walked out and started chewing on some of the grasses on that side of the fence. Jake rushed out and pulled me back by the cinch. “These horses are strong-willed, you gotta keep an eye on them!” Jake remarked.

Hunter’s reply was somewhat unexpected, though: “There’s a guy in town speakin’ at the theatre. His entire point is that free will doesn’t exist.”

“Sure doesn’t look like that to me,” was Jake’s final reply, before he jumped onto my back and we headed out.

Western philosophical, religious and even legal systems are built upon the cornerstone of the existence of free will. For instance, what would be the basis to convict someone for a premeditated crime if that person had no other choice but to commit it? We convict based on the fact that the person made a conscious, misguided decision to perpetrate a crime, which is a reflection of that person’s free will. While that concept may seem obvious to most, in recent times there have been remarkable voices in support of the opposite, most of all so in neuroscientific circles.

Robert Sapolsky’s 2023 book Determined: The Science of Life Without Free Will seems to be the culmination of that train of thought. Sapolsky argues that everything is predetermined. He elaborates that point along the lines that we don’t really make any decisions independently, but that every action we take is the inevitable consequence of prior conditions. Everything starts from our genetic makeup. Adding to that, our upbringing, environment and social context all act as prior determinants for our present actions. Even the context we are in in the present, such as the air in the room, has a measurable impact. All of these factors end up being prior conditions to some chemical reactions taking place in the brain, which then determine the action or decision we “think” we are taking.

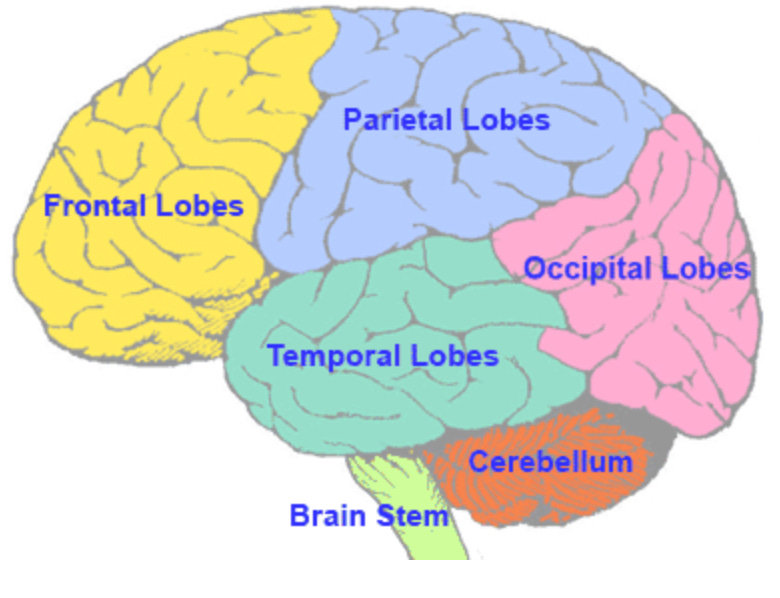

For decades, neuroscience has been obsessed with analyzing the brain as if it were an engine: dissect and dismantle it into ever smaller components and regions, with the inherent belief that if we know what each nut and bolt in the engine does, we will eventually be able to reverse engineer the entire engine. Many versions of maps of the human brain have been published, along with the supposed functionality each of those areas have and a list of conditions that result from damage to the respective area. Researchers have long struggled to identify an area responsible for free will, although recent reports have linked free choice to areas in the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

Sapolsky takes such findings into account, but only to stress that they are the result of past and present preconditioning. He will even go as far as stating that not only free will itself does not exist, but also grit and resilience. In his words,

“(a) grit, character, backbone, tenacity, strong moral compass, willing spirit winning out over weak flesh, are all produced by the PFC; (b) the PFC is made of biological stuff identical to the rest of your brain; (c) your current PFC is the outcome of all that uncontrollable biology interacting with all that uncontrollable environment.”

R. Sapolsky, Determined: The Science of Life Without Free Will

In Sapolsky’s world, we can refer the self, free will, morals, grit, resilience and character all to the dustbin of history, since nothing is more than some preconditioned (electro)biochemistry. All of that biochemistry occurring is merely the result of external conditions past and present, none of which we can control. Given this thesis, it should not surprise that Sapolsky challenges the reader to prove the existence of free will in the light of his own hypothesis:

“In order to prove there’s free will, you have to show me that some behavior just happened out of thin air in the sense of considering all of these biological precursors.”

R. Sapolsky, Determined: The Science of Life Without Free Will

Exactly this challenge is a good place to point out the shortcomings in Sapolsky’s deductions. We will not argue that external factors can have an impact on our decision making. A lot of research has been dedicated to this topic. For instance, judges are significantly more likely to grant parole right after having a meal than on an empty stomach. We will even go along with the fact that the air in the room can have an effect. I trust most of us have been in a meeting in a room that has a stench and have wanted to wrap things up a little faster than usual. So yes, environmental factors can have an effect on our thought process. However, what Sapolsky gets dead wrong is that that does not establish in any way that those factors are the only factors causing decisions. In fact, it does not even prove that they account for a significant portion of the decision making process. The truth may well be that the factors leading into any given decision break down to 85% free will, with some of Sapolsky’s environment and preconditioning making up the remaining fifteen percent.

(Even if you only like 15% of this publication, consider taking the free decision to subscribe, which you can also do for free).

The reason why Sapolsky does not allow for a portion of decision, values and morals to be attributed to concepts such as the self and free will, is because he and the sources he cites are all determined to see the brain as the sole autonomous actor causing thoughts and decisions. Therefore, they need to be able to reduce all morals and decisions to neurobiochemistry. However, that attitude seems a little short-sighted at best. When people walk, they use their feet and legs.* As they are walking, thousands of biochemical reactions are taking place and thousands of electrical impulses are running through the neurons in their feet and legs. Yet we don’t hear many say that “their feet and legs are walking,” do we? Most people will say that it is them who are walking, instead of their feet and legs. So why does it all of a sudden become acceptable to say that “the brain is thinking?” Isn’t it also the persons who are thinking, rather than their brain alone?

Even if we allow for the brain to be the primary cause of all actions and decisions, there are further fallacies in linking all free will or grit to certain areas in the PFC. It may seem enticing to draw the analogy between the brain and an engine indeed. However, the brain is not an engine designed by humans and we cannot yet claim to fully understand its inner workings. We have been able to draw correlations between sections of the brain and certain functions. However, the sentence “correlation is not causation” may be appropriate here, maybe more so than in other contexts where it has recently been used.

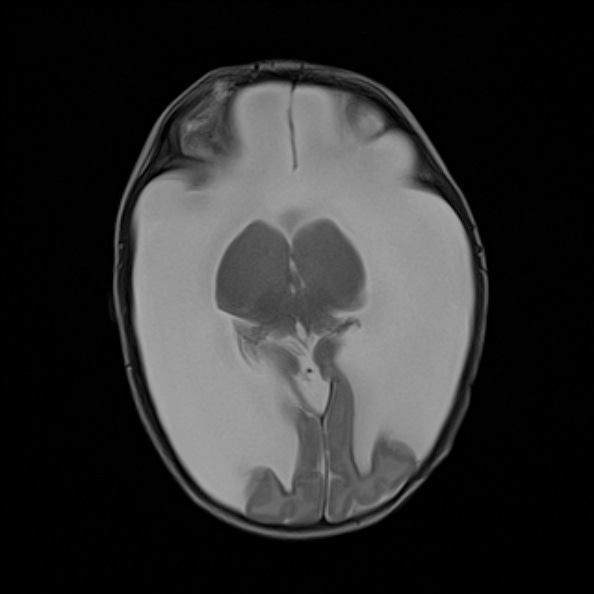

If each area of the brain is linked to certain functions, then the absence of an area should be linked to the absence of the corresponding function, should it not? Well, hydranencephaly is a congenital disorder observed in some infants who are born with some of the brain absent. Instead of brain tissue, their skull contains a sac of cerebrospinal fluid, which mostly consists of ... water. Severe cases of hydranencephaly have low survival rates, but moderate cases have been reported with very unexpected outcomes. For instance, a teenage girl who misses the parts of the brain typically associated with language has been reported to have above average language and communication skills and average-to-high IQ. She was also reported to attend university. If the mechanistic model of the brain were correct, she should have a grave reading impairment.

Sapolsky’s mechanistic view of the brain and the decisions it makes, seems to fall apart upon further scrutiny. Yet he claims that he and his fellow followers of the cult of free will denial are in the “majority.” He will acknowledge that there are those scientists who think that the world is not deterministic and there is free will, but in his words those are “libertarian incompatibilists” who “appear to be a rarity.” The latter is definitely not true in the general public, but it may well be true inside the ivory tower of academia. If so, then another good question becomes why academic neuroscientists who believe in free will are a “rarity.”

We can’t account for each scientist’s opinions, but we can make the following observations. If a tyrant wanted to impose his will on an entire society, wouldn’t it be convenient if the masses were convinced that they had no free will? Likewise, if, let’s say, certain lobby groups wanted to replace merit by empty concepts like “equity” and “social justice,” wouldn’t it be convenient to have “sound science” that states that grit and tenacity do not exist? If they do not exist, they do not need to be rewarded and in that case, there is a “scientific basis” for, say, race or gender based promotion policies. Moreover, if one wanted to pursue a techno-totalitarian regime that created a “human hivemind” by controlling humans’ actions through brain implants, would it not be highly inconvenient if those humans had free will? It would even be more inconvenient if that free will could not be controlled by manipulating brain chemistry, wouldn’t it?

To be clear, we are not saying that either Sapolsky or any of the scientists he cites act malevolently, nor that they are actors in any of the previously cited doom scenarios. It is hard to not see the correlations, though, but then correlation is not causation, is it? However, to try and deny free will so as to establish a “hivemind” in humans is absolutely despicable. Humans are not bees, they are capable of much better (and so are we horses). Just for that reason, we can rest assured that it will never happen.

Free will is one of the oldest concepts, inherently ingrained into our being and societal fabric. In fact, it suffices to tap into one’s own intuition to understand that we have free will. It should, therefore, not come as a surprise that free will sits at the very root of both our religious and legal systems. In the Judaeo-Christian tradition, free will appears in the oldest of scriptures, Genesis. More specifically, it surfaces at the very beginning: in the Garden of Eden. Eve could have decided not to eat the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, but she did. She did so because she had free will. Adam could have prevented her from eating it, but then he just stood by and let her eat it. His doing so is a reflection of his free will. Our legal system is also based upon the existence of free will. There is no need to discern between innocence, a crime of passion, or a premeditated murder, if the perpetrator does not have the liberty to not commit it in the first place.

Our present society tends to make certain analyses overly complicated. Do we really need peer-reviewed papers to answer the question if we have free will? In fact, the answer everybody should come up with intuitively and speedily, is: “OF COURSE, we have free will.” No further research needed. Yet what the scientific elite churns out, is a fallacious methodological framework that leads to the conclusion that everything is predetermined and that all eventually goes back to our genetic makeup. Everything except for gender, that is.

When I want to eat grasses, I do that because it is I who want to eat them. When Jake pulls me back, that happens because he does not want me to run away. It is Jake’s decision, and Jake’s alone. I’m quite sure that not even an empty stomach or dry air would have made Jake allow me to run away. There are also certain things that I know I will never do, no matter what conditions. You can bribe me with a barrel of good beer, you know. But not to do everything. I will readily take Ivermectin, even if it didn’t taste like apples. It is a great dewormer. However, nothing on this planet will make me take a modRNA injection. Not even when the breeze smells like oatmeal all day.

If you like this article, please help us stimulate Substack’s algorithm and click the ♡ button

* I use my hooves, but the same applies.